When Atlanta-based portrait photographer Alex D. Rogers first began photographing guys with cool hair he had no idea the images in his Crown series would end up as a sociopolitical statement that would help others understand Black men’s struggles. Rogers, a New York native, studied video filmmaking for his bachelor’s degree and later went on to get a master’s in instructional design, before moving into still photography after a Janelle Monáe concert. Now, he says, he tells stories in a single frame. Rogers talks to Chill about the Crown series, his inspiration, and experiencing Blackness in America.

Alex, tell me about your inspiration for focusing on Black men’s hair in your Crown series.

My choices for this series were based mostly on a variety of shapes and styles. Part of the reason I began the project was to capture what I’d been seeing online at first — and then in the world around me. Black guys seemed to be more and more willing to try different things with their hair. I’m sure there have always been guys who did. I imagine they were spread out in their cool corners of the world and the Internet brought a lot of them together in one place. It became more normal for this generation as people saw a variety of styles executed in cool ways more often. There have been periods in American history where Black men made more “daring” choices with their hair, but that seemed to have slowed in the ‘90s and early 2000s. Some of the hairstyles and colors worn by Black men today would have been the source of ridicule in the not-so-distant past.

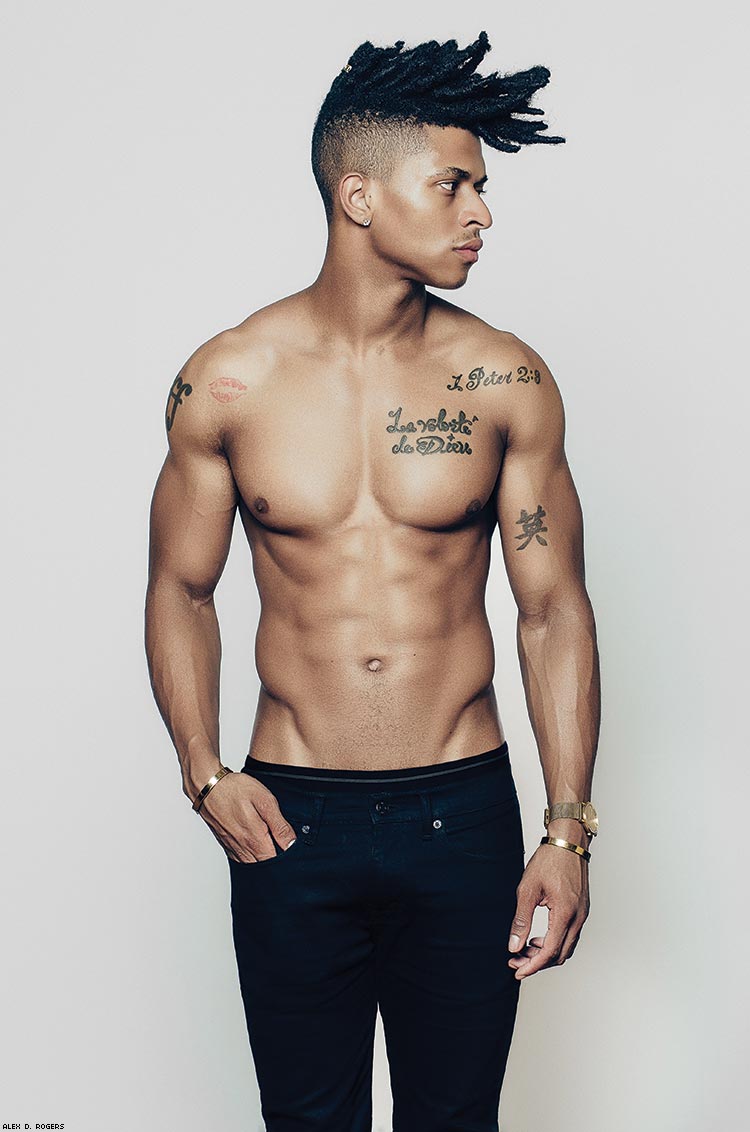

Randy: Shorter locs that were formed into a sort-of Mohawk. They have since been cut.

Randy: Shorter locs that were formed into a sort-of Mohawk. They have since been cut.

We rarely talk about Black men’s hair in the same way — or with the same scrutiny — as we do Black women’s. Why is that?

I’m not exactly sure why the conversation around Black women’s hair is so much louder than that of Black men’s. It could be that Black men haven’t been faced with the notion that they should adhere a certain standard of beauty as it relates to their hair in ways that Black women have. On the contrary, Black women haven’t been faced with the notion that they should maintain a certain appearance of masculinity in order to avoid being preyed upon. One thing I know for sure is that we police women’s bodies and choices a lot more, in general.

Yes, and American “beauty standards” have often been at odds with Black hair to begin with.

I’ve been aware of the bias associated with Black hair my entire life, but it was amplified as a few of my subjects were forced to cut their hair to gain or retain employment. That cast a darker shadow over the project pretty early on. Some of these guys had a connection with their hair that they were forced to part with to be able to get jobs. Cutting their hair didn’t make them better at their jobs. It made their physical appearance more acceptable to their employers. That was sobering.

Wow, that provides a really different perspective.

The meaning of the project broadened from there. I went from capturing something that I thought was cool to feeling like I was making a case for accepting different forms of beauty. This was occurring as instances of police brutality were more widely reported on and Black Lives Matter was gaining prominence. I was becoming more aware of my Blackness in America than I had ever been as an adult. While the original intention for the project was to present ordinary Black men as these sort of artful versions of themselves, it also became a sort of bait and switch to help other people understand our struggles. I had these beautiful portraits that sometimes told heartbreaking stories.

Phill: Worn as a curly afro during the sittings, his hair is sometimes braided or pulled back into a ponytail.

Phill: Worn as a curly afro during the sittings, his hair is sometimes braided or pulled back into a ponytail.

How have people responded to the Crown series?

One thing that really struck me was the way people reacted to the stories of these guys when I presented some of the photos at a local art stroll. In general, people would remark about how beautiful and interesting the hair was. Once they learned about how the subjects were forced to cut their hair to conform to bias, they were dumbfounded. I could tell that I’d exposed them to a concept they hadn’t ever given much thought to — something they never had to think about before that day. That was pretty fulfilling.

Did you grow up going to a Black barbershop?

I did not grow up going to the barbershop. As far back as I can remember my parents cut my hair. I wore it long for a lot of my life, too. It wasn’t until later in high school that I remember going to a barbershop regularly. I grew it out again in college and wore braids and eventually locs. After my senior prom, I didn’t get another haircut until just before the time that I picked up a camera, ironically.

I don’t know that I missed having that barbershop experience, because there were other places — like church — where I was exposed to social environments with other Black men. I recognize that a church can be a pretty homogeneous social experience in and of itself, though. I’m definitely intrigued by the barbershop dynamic. It’s very easy to be my natural fly-on-the-wall self there. I just watch and just listen.

I heard a Janelle Monáe concert hooked you on photography.

That is true. I’d been a huge fan of Monáe’s shows after having seen her play a few times around Atlanta. Back in 2010, she played a two-night show in support of her major label debut album. I decided — on a whim — to purchase a better camera in time for [it]. I had no clue what I was doing. Most of photos were not that great. But the ones that did turn out were what hooked me. The fact that she’s such a dynamic performer probably had everything to do with that. I don’t photograph as many live shows as I’d like to, but artists are my favorite subject. It’s even more fulfilling when they are intentional about how they want to portray themselves or their message visually, like Monáe is.

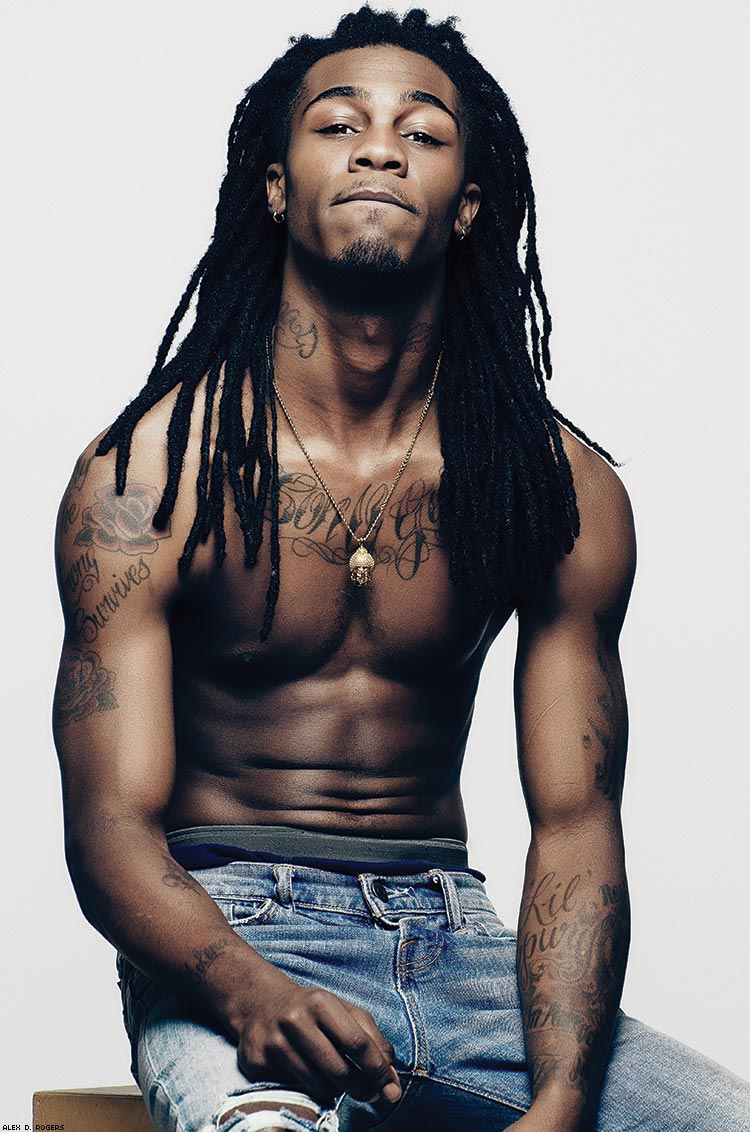

Sydell: Long locs that have since been cut.

Sydell: Long locs that have since been cut.

Why is it important to center people of color in your work?

Over the years, I accumulated a pretty large collection of reference images from fashion editorials. At one point, I realized that of these thousands of photos, only a small percentage included subjects of color. I’d like to help fill someone’s reference folder with great quality images of beautiful people of color one day. …

It [is] important to produce work that [portrays] people of color in the ways that I’d seen them in those thousands of reference images I’d saved. What it all boils down to is representation. I try my best to avoid stereotypes in my portraits. I want people to feel proud when they see my work — whether they’re the subject of the image or not.

How does being in Atlanta play a role in your work?

In general, I think being in Atlanta helps me a lot on the business side. I really enjoy the niche that I’ve been able to plug into here. And there’s no shortage of musicians and artists.

Why is entrepreneurship important for men of color?

Simply put, I don’t believe there’s a more effective way to level the playing field — in terms of opportunity — than to actually be one of the ones handing them out.

What’s next for you?

I love personal commissions, but ultimately I’d like to focus more on photographing artists for publications as well as their projects. I do most of my work in my studio here in Atlanta. I really enjoy working with up-and-coming artists and the budget isn’t always there to cart me and all my equipment around. I don’t mind it, though. Like with Janelle Monáe at those shows on the eve of her big national debut, there’s an energy that you just don’t get in other situations.

There’s a photographer named Richard Corman who recently published a book of portraits he’d taken of Madonna in 1983 before she became Madonna. I always joke that in 30 years, I want to be one of those guys who has a folder full of portraits on an old hard drive of an artist who turned out to be just as groundbreaking.

READER COMMENTS (