Sadness and suffering are as engrained into Mexican culture as tacos and cerveza, and one doesn’t have to dig too deep to understand why. For Mexican-Americans — who as a culture know well the struggles of immigration, poverty, systematic racism, gang violence, incarceration, and religion-fueled oppression — being sad almost seems like our birthright. It’s as though the very expression of our suffering is the only way we know how to cope with it as a people.

Expression of grief is done many ways in Mexican-American culture: tattooed teardrops to symbolize prison time or other traumas, the popularity of nicknames like “Sad Clown” among gang members, and, of course, the longsuffering Christ of Catholicism.

In the art world, artists like Frida Kahlo have become exalted saints due, at least in part, to their connection to suffering. Kahlo was severely injured as a teen and suffered crippling physical pain and emotional anguish (not to mention 32 surgeries) throughout her life.

Through these symbols of sadness, one gets to express that, despite the brave face put on every day in order to survive, they too, suffer.

Somehow this shared experience comforts and unites us. We know we are not alone in our struggles. And one of the most powerful ways to express emotion and connect with others as a culture is through music.

“As a Smiths [and] Cure fan and a Latina, I can say that it’s reminiscent of what I grew up listing to in Spanish from my parents’ choice of music during the ‘80s,” a 39-year-old Latina and mother from Costa Mesa, Calif., tells Chill. “Like, the emotion. I’ve analyzed this for our family and we agree that is why we are fans. The emotion in the music is similar to [what] our parents listened to and those kinds of whiny male vocals we enjoy.”

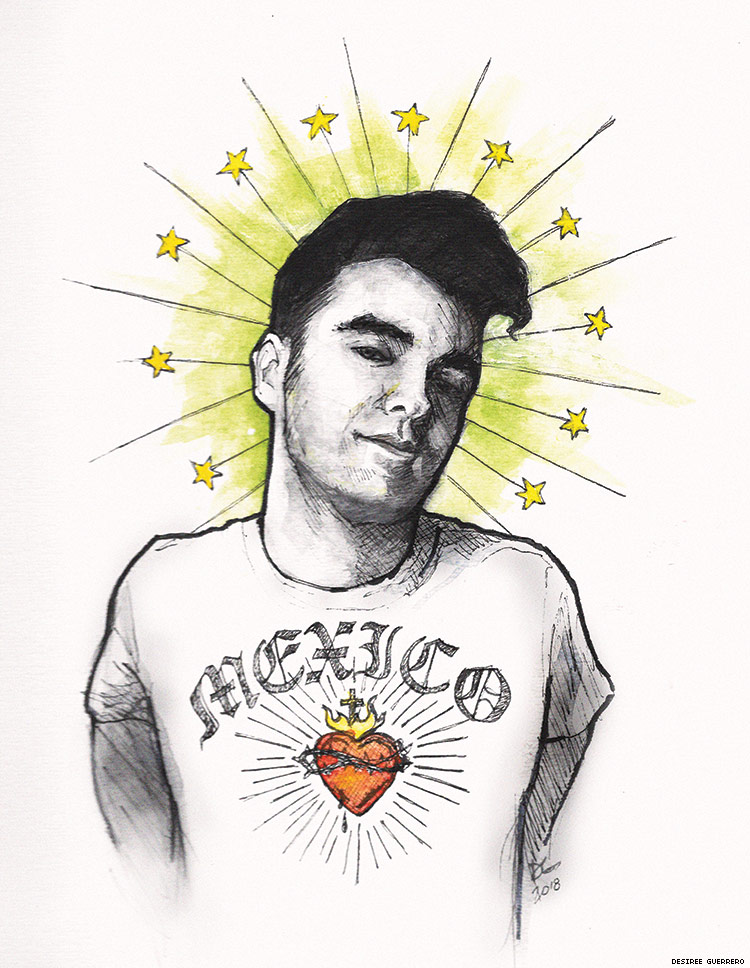

Like myself, she represents a very specific kind of music fan that exists in large numbers in the greater Los Angeles area — the post-punk-alternative-loving Mexican-American. If that mouthful doesn’t really explain much, just think Mexican-American fans of The Cure, The Smiths, Depeche Mode, etc. I would simply refer to someone like this as a fellow “Mexican Smiths’ fan.” And The Smiths, or more specifically, their former frontman Steven Patrick Morrissey, is the nearly unanimous favorite amongst this sect. At this point, much like Kahlo, he’s practically an exalted saint.

I am certainly not the first to wax philosophical about the ongoing love affair between Morrissey and his Latinx fans, and even about the very specific connection between Mexican-American fans and the singer. In fact, this comparison to the “whiney” ranchera music popular in our parents’ generation has been made by others who are deep in the scene.

“As in ranchera, Morrissey’s lyrics rely on ambiguity, powerful imagery, and metaphors,” Gustavo Arellano writes in his book Ask a Mexican, based on his popular, long-running weekly column of the same name in the OC Weekly. “Thematically, the idealization of a simpler life and a rejection of all things bourgeois come from a populist impulse common to ranchera.”

Morrissey often sings of being an Irish immigrant in an imperialistic society (England) that looks down on his people yet relies on them to supply cheap labor. Naturally, that strikes Mexican-Americans as a familiar experience. There are other cultural similarities Irish and Mexican people share, as well: a strong work ethic, a love of boxing, and being devout Catholics.

“You see these stereotypical tough guys, Latino men covered in tats, having these great emotional outpourings to his music, completely reduced to tears by a beautiful song like ‘Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want,’” explained José Maldonado to NME.com last year. Frontman of one of the world’s most popular and enduring Smiths-Morrissey tribute bands, The Sweet and Tender Hooligans (sweetandtenderhooligans.com), Maldonado says, “It’s really moving — and for a lot of people — quite unexpected.”

I’ve attended several Sweet and Tender Hooligans shows and can attest to the passion their fans have about this music. They are as enthusiastic as if they were seeing the real thing. They sing every word together — and cry together.

Unlike ranchera musicians, Morrissey has a history of sexual ambiguity (although he has often distanced himself from the LGBTQ community and once considered himself asexual). There is definitely an element of rebellion against traditional Latino machismo in choosing an effeminate, emotionally-complicated Brit as one’s musical god.

The fact that Morrissey is white is very relevant too. He is specifically popular among second and third generation Mexican-Americans who grew up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, some of whom are mixed race or don’t speak Spanish. In the mashup of cultural influences that these in-betweeners grew up with, this is, in many ways, an attempt to create a community of their own — a place where they feel like they belong and are accepted just as they are.

“Being raised in a country where you’re supposed to be an American, but you’re Mexican culturally, you’re kind of between two things,” Marina Garcia-Vasquez of Mex and the City, a New York City-based online community for Mexican-Americans, told Public Radio International (PRI). “You can’t really relate to your own family because you have your own interests.

Maldonado agrees: “Amongst my Anglo friends, I wasn’t quite Anglo enough. And around my Mexican friends, I wasn’t quite Mexican enough. I didn’t really fit into either compartment, so to speak.”

Despite the number of Latinx Morrissey fans, there are also detractors. For example, naming his compilation of music videos ¡Oye, Estéban! led some to suggest the entertainer is a cultural appropriator with purely self-serving motives.

Morrissey has expressed his love and appreciation of his Mexican-American fans many times over the years — albeit sometimes in questionable ways. During his 1999 ¡Oye, Estéban! tour, Morrissey famously “confessed” to his almost completely Mexican-American Southern California audience, “I wish I was born Mexican, but it’s too late for that now.”

Then there was this famously strange and somewhat condescending praise: “I really like Mexican people. I find them so terribly nice. And they have fantastic hair, and fantastic skin, and usually really good teeth.”

At another concert in Mexico, Fernando Lions, a Brooklyn-based tattoo artist and devoted Morrissey fan told PRI that the singer did something that left him not knowing exactly how to feel. “He had taken the Mexican flag and had put it around his waist, like a dress, or a skirt, or a towel… It was sort of rude, but sort of sweet. It was really odd.”

Then, Morrissey had the cojones to touch on gang violence in our community with the song, “First of the Gang to Die.” But, as someone who actually lost her first love in exactly this way, I must admit the song is sensitively and artfully done. It feels more like a delicate tribute to the fallen rather than an exploitation.

Still, accusations of cultural appropriation and pandering to his audience are plausible, considering that his music has been increasingly peppered with Latin themes, sounds, and language throughout his solo career. Yet, no matter how much negative press the singer seems to receive, his Mexican-American fanbase is as loyal as ever, although they are aging along with the 59-year old.

The popularity of Morrissey and other musicians of this genre peaked in the 1990s, and new fans hopping onto the sad-wagon have slowed over the years. As we moved into the 2000s, the concept went commercial — one could simply purchase the rebellious “look” of Smiths-loving Mexicans via mass-produced T-shirts at one’s local Hot Topic, without ever attending a show or hearing a single song.

Today, Mexican-American youth seem to be grasping onto different, dare I say, happier, musical genres. Aside from a shift in ideas, trends, and attitudes, I think that many of today’s woke millennials simply don’t have the patience for crusty old curmudgeons who occasionally spew offensive bullshit (which even the most diehard fan at this point must admit Morrissey has done). It’s the #TimesUp, #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter generation, one weary of old white men, and prefer to get their Latin-inspired music directly from Latinx artists.

But rather than desperately cling to our perpetual sadness, as I and my Morrissey-loving-breed of Mexican-Americans begin to lose relevance, I choose to see this as progress. Perhaps the younger generation of Mexican-Americans is feeling more empowered and less imprisoned. Perhaps, for many, there is simply less to cry about.

Then again, under the Trump administration — which wants to deport, incarcerate, and separate us from our families — we are learning just how much we still have to mourn.

And Maldonado tells Chill he sees a surprising number of new, younger fans at Sweet and Tender shows each year. “You definitely see a mix of all ages at our shows over the last 25 years, but it’s striking how many young people you still see discovering those songs for the first time. It definitely speaks to how they can relate to many of the themes in Morrissey’s music.”

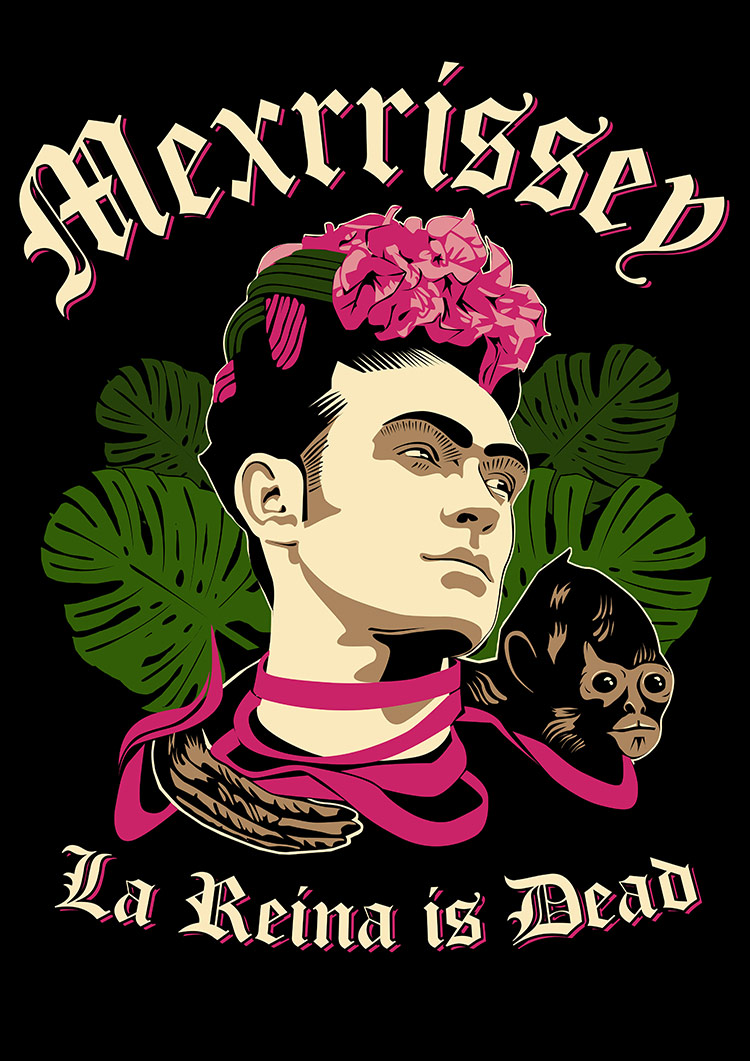

As a whole, the cult of Morrissey doesn’t appear to be losing any momentum. In fact, Mexican-indie supergroup Mexrrissey (mexrrissey.com), comprised of seven popular Mexican indie musicians, released the critically acclaimed No Manchester in 2016 — an album of Morrissey songs that have been translated into Spanish and “Mexicanized,” with added layers of mariachi, cumbia, and bolero — and continue to tour due to its wild popularity.

“I plan on continuing with our tribute to Morrissey [and] The Smiths for as long as my body will allow,” confesses Maldonado. “I enjoy playing with my bandmates and singing to a cheering audience every bit as much as I did on that first gig in October 1992. I’m 10 years younger than Morrissey, so I suppose I could at least keep it going for another 10 years after he decides to hang it up. ‘One Day, Goodbye Will Be Farewell,’” he says, quoting a Morrissey song title. “Just not anytime soon.”

READER COMMENTS (