“The pediatrician said you need to come to the office immediately,” my mom quivered over the phone. Hearing “immediately” commanded my heart to double time, and my stomach felt like it was being flushed down the toilet.

The week before, I’d had a routine physical, and the doctor noticed large, swollen lymph nodes around my neck and in my groin area and that I had started to feel dizzy after standing up for more than 30 seconds. We arrived to my pediatrician’s office 20 minutes later, and he quickly guided us to a room and handed me a paper gown. He was acting almost like he had to get this news off his chest. My doctor at the time was finishing his last year of residency, and he was still learning how to handle tough news. This was my first check-up with him since the pediatrician I had known for years had moved to another office. Changing in front of my mother that day seemed worse than any other day. First my hat, shirt, pants, then underwear — every layer came with an expectation to be vulnerable and accountable for whatever this “news” was my doctor had for me.

“Hey Kaleb, so how are you feeling?” my doctor asked with tears cradled in his eyes.

“I’m fine,” I replied with a smile on my face. Since I saw that my mother and now my doctor were on the edge of erupting with emotion, I was forced to be strong for them. And tears? Who has time for that.

“Oh, OK, that’s good. Well, this is my first time delivering this news ,so I apologize if this does not come out the best way,” he said as his right hand braced his angsty, shaky left hand by the wrist.

“Well, your test came back positive for HIV. We didn’t get enough blood for the test, but we still ran it. So, I want to draw more blood to confirm the test, and I will refer you to the Infectious Disease Clinic.”

My mother’s eyes darted to me and she gushed out a fountain of tears. Everything felt colder, and I could not move or even emit a facial expression to react to the news. My mind sped back to those salacious, quick nights of lust. I remembered every house, hotel and condo I had visited during the past two years. I had been trying to cope with my actions without being accountable for them in that moment. Now, I couldn’t escape this anymore, and that realization numbed me. Remembering every man that I gave my body to consolidated my stillness.

My mother stayed with me in the hospital for a week and supported me through two weeks of home treatment. Being diagnosed less than two months before I started college was depressing. I didn’t understand the gravity of the situation until I was in the hospital. If I would have gone off to college in the Midwest without being diagnosed, the winter would likely have killed me. Large doses of penicillin being pushed into my bloodstream by the hour made it hard to eat. Every time I ate, it felt like someone was inside of me pushing the food back up. I thought that giving up and dying from this stigmatized virus would be easier than waking up each day to fight for my life.

“Come on Kaleb, let’s do this,” my mom said as she raised my hospital bed.

“Can I just go back to sleep?” I responded as defeat consumed the little motivation I had to get out of bed to walk or to even shower.

“No, you need to eat. I’m not going to let you give up.” She opened the tray of nauseating hospital food. Watching her spread ketchup on the hamburger bun was worse than the smell of it. She stabbed the lettuce doused in Italian dressing making sure to pick up a tomato and carrot on the way to my mouth. Her need to see me be healthy inspired me to get better for my loved ones, even if I did not feel like I was worthy enough to live.

The Real Fight Begins

Two months later, I arrived to campus 50 pounds heavier, with a 90-day prescription of meds and angst that this transition into independence and accountability would be smooth. August 20, 2016, was the longest day ever. When I finally reached for the navy sheets, comforters and my Power Rangers pillow to make up my dormitory bed, it was 11:47 p.m. I bolted to the nearest bag of Nacho Cheese Doritos and bottle of water on my desk, punched the bag open to scarf down a couple chips and sprinted to the dresser to get one of my pills.

This is what many nights at college would be like — almost forgetting to take the medicine that was keeping me alive. I also had to make sure every meal was balanced in proportions and included vegetables, and each week I had to schedule an hour or two to exercise. All of these tasks that are instrumental to living a healthy life seemed so tedious on top of adjusting to predominantly white spaces, rigorous courses, and a suffocating, new social environment. At the dining hall with friends, I was afraid to take my medicine at dinner, because I knew they would question me. Most of my friends on campus were black, and I was aware of the stigma and stereotypes thrown on those in our community living with HIV. I knew my identity as a black man in Indiana would be under attack, but adding that I am gay and HIV positive, I struggled with being my authentic self in the first few months of college.

After one too many nights of forgetting to take my medicine, I set a daily alarm on my phone at 10 p.m. to remind me. I also started leaving my room in the morning with one pill in my book bag so when the alarm went off, I would not have to sprint across campus to take it.

The more I accepted myself and my health improved, I started feeling comfortable taking my pills in front of my friends. One night at my crew’s normal 7 o’clock dinner, someone new came and sat with us. I took my pill out, ready to take it, and she asked, “What do you take medicine for, Kaleb?” Everyone darted their eyes my way, and I responded saying, “I have HIV.” I had swallowed all that stigma along with my pill and I was able to open up about my status to my friends. Shockingly, one of my friends responded, “Thanks for being brave to tell us. Is there any way we can support you?” In that moment I felt finally comfortable with my status.

The Aftermath of Trump’s Election

“O beautiful for spacious skies, for amber waves of grain.” I walked out of my political science class the day after the presidential election and was stunned to hear “America the Beautiful” blasting from a white fraternity house. As I neared the house, students were waving a “Make America Great Again” flag and the U.S flag. They were having a party, a celebration for the newly elected president. I stood in the courtyard watching them rejoice and flail their bodies to Chance the Rapper, and a charge of confidence spiked in my mind. The election of Donald Trump was a direct attack on my identity, and the bills and orders his administration would enact would further oppress that identity. Trump’s election to office was a war declaration. This instantaneous shift encouraged me to think about more than just surviving but how to thrive in an environment expecting to see me whimper and assimilate. I not only needed to be strong for myself but for other people of color.

HIV, Back Up Off Of Me

I started hosting workshops on sex positivity and healthy relationships in an organization on campus called Queer Students of Color. My role to educate others within my community was important to understand the plight of one another and in learning to support each other in these tumultuous times. I was invited by a multicultural fraternity to share my story as a person living with HIV.

I also decided to run for the executive board of student government. This election was starkly different from ones in the past because a great number of students of color were running. When we discovered that we were all candidates, we met in the student union and planned to advertise together, posting each other’s ads on our own social media platforms and promote the candidates through the Association of African American Students. A week later, the seats were filled in our great hall on campus for election debates. We sat together, and the audience was filled with other people of color representing their organizations and showing their support. After the votes were tallied, the executive board of our student government now has a people of color majority. Seniors cried as we took our election pictures, and that night history was made. This allyship among people of color was rare, and together we fought for solidarity and for representation.

My story does not represent the plight of all those living with HIV. My story is one of redemption and victory, not shame. I tell it to reduce the stigma and encourage others living with HIV. I tell it to educate and expand the social consciousness of those not living with HIV. I went into my first year of college with little doubt that I would be dead by the end of my first semester. Every day, I wake up reminding myself that I am worthy of living the life I am building for myself. I fight for that every day.

To those teens living with HIV, you deserve to live. Some days will be hard and you may feel guilty because of your condition. Know that forgiving yourself and embracing your plight will make you stronger, and nothing will be able to stop you. Surround yourself with friends and family who will uplift you and be patient with those learning the terminology and the quirks to our condition. Set an alarm to remember to take your pills daily, get tested for other sexually transmitted diseases every three months, and if you ever have any questions reach out to your doctor or health educator.

You will thrive! I believe in you.

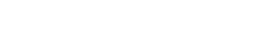

Kaleb Anderson is a 19-year-old sophomore at DePauw University with a political science/Africana studies double major. The Atlanta native is also an alumni intern at VOX Teen Communications, a 24-year-old teen-driven nonprofit based in downtown Atlanta that promotes uncensored self expression and assists with journalism, leadership and facilitation skill-building. This story was originally published on VOXATL.com, here.

READER COMMENTS (