In our current moment there has been considerable debate around what is frequently referred to as “sexual racism,” a term that reacts to the romantic and erotic rejection of men of color by white gay men. These discussions describe, often in detail, the various forms of emotional injury in the digital realm of dating and hookup apps that manifest a kind of modern-day Jim Crowism. Black gay men know as well as anyone that the sexual liberation of white gay men has not made them more sensitive to racism.

However, what’s less discussed now is the sexual objectification of black men by white gay men. These debates seemed to explode around the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and his images of black men in the 1980s, at the height of the cultural wars. Even as his work was championed and defended by the white art world for its transgressive themes, there were others who took issue with his depictions of black men. This was not simply an argument between those who favored censorship and those who favored free expression. Or those who were appalled by sexually provocative images and those who were not. This was a debate that centered around race and power, art and representation — and it was a debate led by black queer men. This is also a debate we continue to have today.

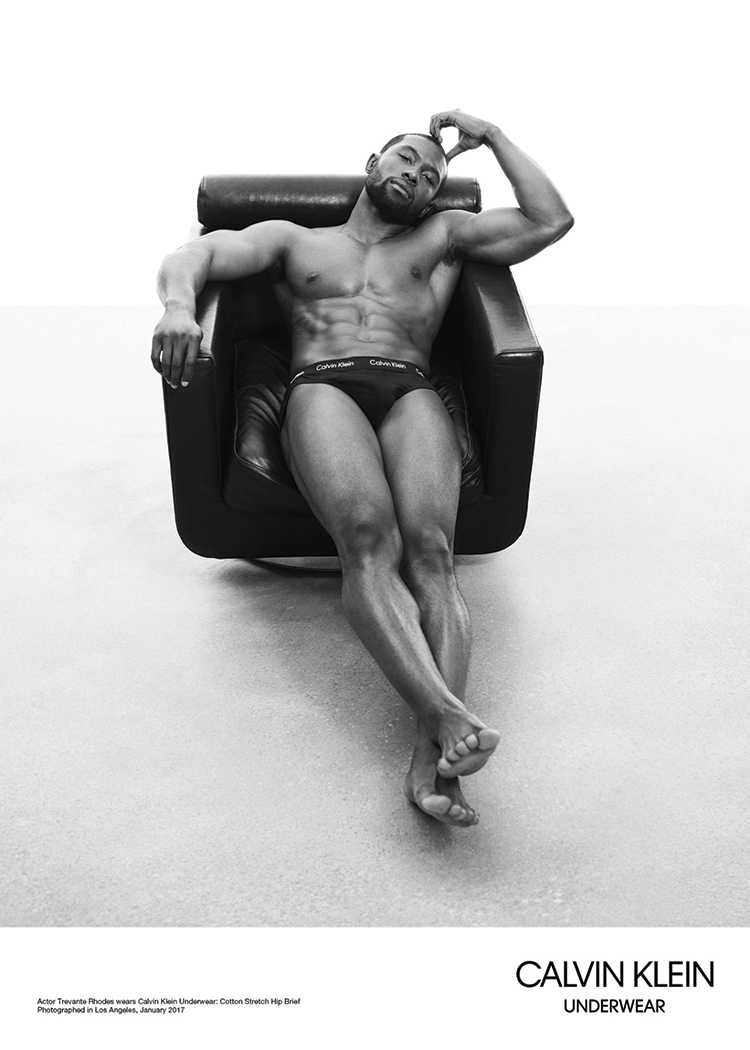

Mapplethorpe casts a long shadow over discussions around race and desire, and around black men and sexuality. So much so that one cannot celebrate the new Calvin Klein underwear campaign featuring the actors from the film Moonlight without acknowledging that Mapplethorpe’s presence lurks just beneath the surface. Styled by Olivier Rizzo and photographed by Willy Vanderperre, the ad campaign features Mahershala Ali, Trevante Rhodes, Ashton Sanders, and Alex R. Hibbert. The choice to include Hibbert, who is only 12, is an interesting one, considering the erotically charged nature of the campaign and the company’s history of being criticized for bordering dangerously close to sexualizing minors.

But Rhodes and Ali are absolutely Mapplethorpian: dark-skinned, masculine, physically fit black men, their stunning bodies set against black-and-white photography, which has caused quite a stir. Rhodes’s pose in particular, recalls Faye Dunaway’s iconic pose the day after she won the Oscar for her role in the film Network. Her pose reinforces a particular narrative of white womanhood: leisurely, privileged, pampered and bored, as much as Rhodes’s pose amplifies his limbs and coolness.

The triumph of the Calvin Klein campaign is that it elevates the brilliant actors above that catastrophic Oscars night. And Vanderperre’s delicate camera is far less punishing than Mapplethorpe’s rational, clinical, detached one. The perfection sought by Mapplethorpe was inherently a sadistic enterprise. This motivation mixed with the race of his models culminated in an almost anthropological obsession with black male genitals. Elevating beauty is less the goal than displaying the sexual differences between races. Scientific racism is never far from sexual racism, and photography has at times been a dark art in service to both.

No image speaks to this point about objectification better than one of Mapplethorpe’s most famous and certainly most infamous images: Man in Polyester Suit. The model was Milton Moore, wearing a tight suit with his long black uncircumcised penis dangling out the zipper like an elephant’s trunk. His face is not in the frame, so we only see his body in fragments.

Writer Edmund White, in defense of Mapplethorpe, argues that many of his models, including Moore, were in fact his lovers, and Moore in particular requested rhat his face and penis not appear in the same image. However, having sex with black men does not exclude a white man from racism, and in the case of Mapplethorpe, black men were not only a fetish but racism itself.

More about the Calvin Klein campaign: The bodies are arguably more humanized; their faces are more prominent than their genitals. And yet, even as we are compelled to look at Ali, Rhodes, and Sanders, we are also compelled to see the dynamics of race. This is again Mapplethorpe’s phantom.

Mapplethorpe’s greatest critic, the black gay poet and essayist Essex Hemphill, took him on directly, offering the critique that his work objectified black gay men. He launched these arguments like grenades in his essay, “Does Your Momma Know About Me,” shethering* Mapplethorpe in the work to pieces. Such a critique may be taken for granted now, but for the time, Hemphill’s dissent was extraordinary. Other black gay men engaged in critical and artistic conversation around Mapplethorpe’s work include Kobena Mercer, Isaac Julien, and Ajamu X. A discourse developed from both sides of the Atlantic, led by black queer men challenging Mapplethorpe.

These debates were critical because they provided a frame and lens to think about race, sexuality, and art in ways that challenged accepted assumptions and practices. This effort, led by black queer men in the United States and the United Kingdom, provided not only the framework but the blueprints for contemporary discussions around this topic. We can look to these past efforts for inspiration, guidance and most critically, language.

*Ethering is reference to a Nas/Jay-Z musical battle. It’s now a term referencing “a situation where you think somebody won a battle” per Urban Dictionary. Adding the SH makes it feminine.

CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. Founder and executive director of the Counter Narrative Project, Stephens coedited the anthology Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call, and his work has appeared in Georgia Voice, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Lambda Literary Review, Creative Loafing, and RH Reality Check, among others. Follow him on Twitter @charlesdotsteph.

READER COMMENTS (