During the 1992 presidential primaries, Pat Buchanan, seeking the Republican Party's nomination, used an unauthorized clip from Tongues Untied to blast the National Endowment for the Arts and attack George H. W. Bush.

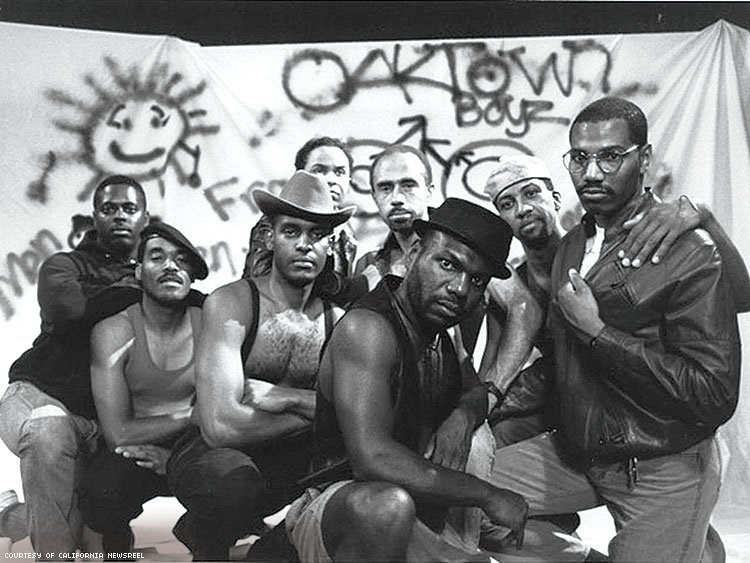

Documentary filmmaker Marlon Riggs’s masterpiece — exploring black gay identity and experience through storytelling, poetry, movement, and expression — premiered on PBS the year before. At least 17 stations refused to air it.

The controversy surrounding the work revolved around some profanity, a drawing of a penis, and depictions of black men kissing. Buchanan, the Christian Coalition, and the American Family Association sought to use the film to defund the NEA.

Tongues Untied would become weaponized in the culture war. The brilliant work was condemned as pornography by the right wing and debated in the halls of Congress, when Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina used it to argue against funding the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Despite the fact that only $5,000 in NEA funds was used to produce Tongues Untied, the film became front and center in the debate against arts funding. And Riggs became the lightning rod.

Riggs — a talented master of rhetoric himself, and far from a shrinking violet — fired back with an op-ed in The New York Times. In “Meet the New Willie Horton,” he accused Buchanan of “ruthless exploitation of race and sexuality to win high public office.” (Riggs was referring to a deeply racist and exploitive ad run by Bush’s 1988 campaign against Michael Dukakis. It insinuated that the then-governor was responsible for letting convicted killer Horton out of jail, only for him to rape a woman and assault her fiancé.)

By framing himself as “the new Willie Horton,” Riggs recast the public narrative from arts funding to how America’s racist fears are exploited by politicians. The condemnation of Tongues Untied was not just about art, but about stoking white fears of black sexuality. White fear has been a winning strategy for conservative politicians since the birth of American democracy. And it is still working.

For Riggs, who was a prophet as much as an artist, the culture war waged against him — and the blatant distortion of his work — was never just about arts funding; it was always about race, always about sexuality.

Riggs was the rare black artist who created work not for white pity or pleasure, but for black affirmation. This is how a black artist responds to a repressive regime. Tongues Untied is exemplary of this, but it’s not his only work. In his stunning nonfiction films, Riggs provides a people’s history of 1980s and ’90s AIDS activism. In No Regret, for example, black gay men tell their stories and speak candidly about HIV. This counters the prevailing notion, from movement history gatekeepers, that black people were mostly silent around HIV in the early days of the epidemic. Riggs’s work provides both evidence and testimony of our existence. We fought on the frontlines, too.

Like his contemporaries of the era, Craig Harris and Joseph Beam, Riggs was a pro-feminist black gay man whose work, particularly Black Is... Black Ain’t, might be viewed as one of the early foundational texts of intersectionality. Black Is… features such acclaimed scholars and activists as bell hooks, Angela Davis, Cornel West, and Essex Hemphill; critiquing the contours and borders of black identity and imagining broader and more inclusive possibilities of our race.

I am troubled that a lot of emerging black HIV activists don’t know about Riggs and his legacy. Whenever someone says “there isn’t a black community, but black communities,” they are in part invoking his legacy.

CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. The founder and executive director of the Counter Narrative Project, Stephens co-edited the anthology Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call and his work has appeared in Georgia Voice, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Lambda Literary Review, Creative Loafing, and RH Reality Check, among others.

CHARLES STEPHENS is an Atlanta-based writer and activist. The founder and executive director of the Counter Narrative Project, Stephens co-edited the anthology Black Gay Genius: Answering Joseph Beam’s Call and his work has appeared in Georgia Voice, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Lambda Literary Review, Creative Loafing, and RH Reality Check, among others.

@charlesdotsteph

READER COMMENTS (